The Real Reason We Won’t Get the Chevy Montana in the U.S.? CAFE.

Yes, the new Montana small truck is all kinds of awesome. No, we’re probably never going to get it in the USA. Why? It’s not because of the name (which is awesome), nor is it due to the 133 HP 1.2L three-cylinder turbo (less awesome), or even the fact that it’ll be front-wheel drive only. The real reason we won’t see a truck that’s “actually small” like the Montana is CAFE, the Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards. Here’s the skinny.

First: how small is small? For an American truck, the Montana is small, but not as small as trucks used to be in the US. At around 185 inches, the Montana is significantly shorter and narrower than a Ford Maverick which is nearly 200 inches long. It may not be as small as Toyota’s first pickup truck sold in US which was **tiny** at 169 inches long, but for the current market it’s practically pocket sized. At this point many of you might be thinking: what’s wrong with that? Afterall, many of us (myself included) would love the option of a small, efficient truck. So where’s the catch? Well, it’s in that small and efficient combination. It’s too small and not efficient enough and that’s all because of CAFE.

Back to that Maverick for a second. It’s a great truck, but at 199.7 inches long and 73 inches wide, it’s not really what I’d call small. Unless you also think a Ford Explorer or a Dodge Durango with a 6.4L V8 is “small,” in which case, you do you. The reality is that for fuel economy compliance the Maverick and Ranger are essentially in the same category and that standard hybrid allows the Maverick to make sense. Why then couldn’t the same tricks apply to the Montana? Let’s dive in.

How does CAFE work anyway? Glad you asked.

34a Gas Shortage Sign in Connecticut During Energy Crisis 892×600

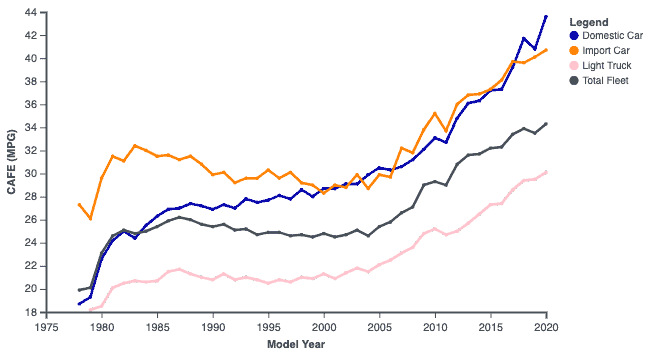

First created in 1975, CAFE sets standards for passenger car and light truck fuel economy. This was part of America’s response to the oil embargo and other oil supply related issues that plagued the early 1970s. The aim was simple: make vehicles more efficient so that America would use less gasoline and therefore import less oil reducing our dependence on foreign production. To do this CAFE created minimum MPG targets for cars and trucks and introduced fines that were levied against vehicles that failed to comply.

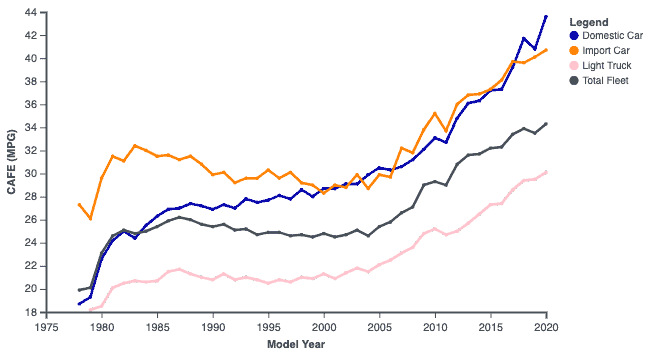

Initially CAFE had a reasonable impact on average fuel economy. Companies invested in more efficient designs, reduced engine displacements, retired older and inefficient designs, etc. Americans also started to favor more efficient vehicles made by foreign companies and we saw the rise of Toyota, Honda, and even Volkswagen. But as always, consumer’s memories are short and the trend towards increasing fuel economy was fleeting. Bu 1985 progress had plateaued or even declined in some categories. But it was the 1980s and the oil embargo seemed a long way off.

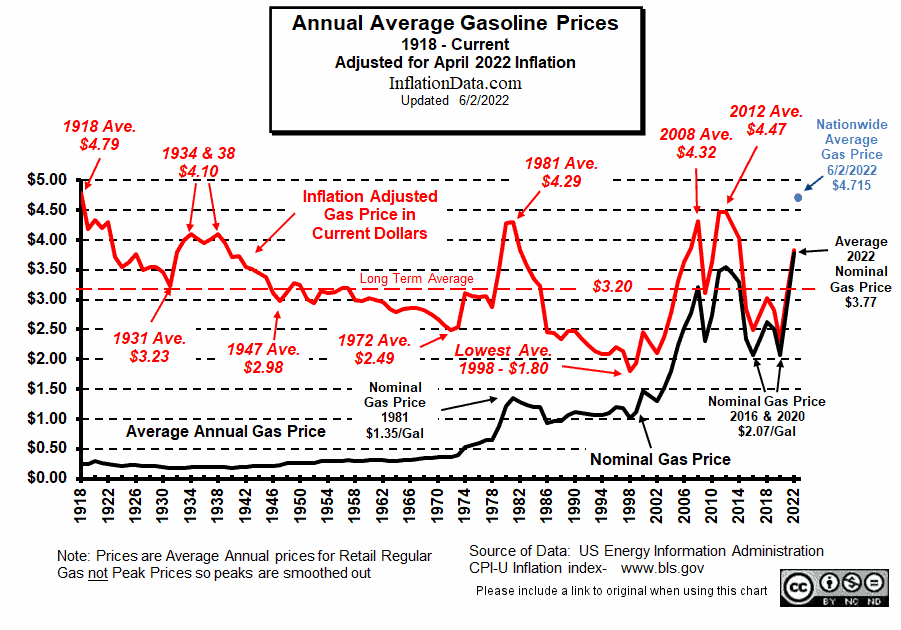

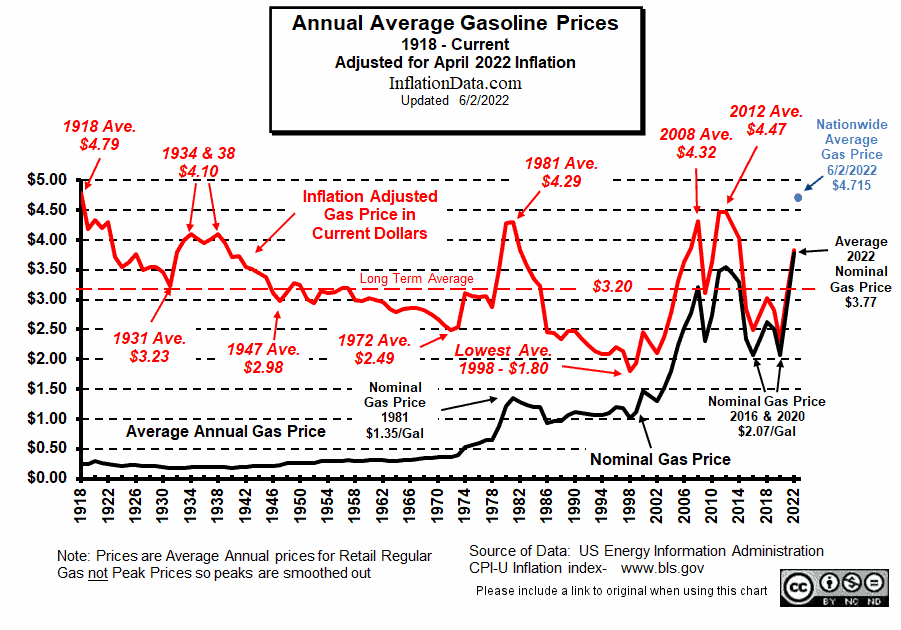

By the 1990s America had well and truly caught truck and SUV fever. Sales of sedans started sliding and car companies couldn’t produce bigger trucks and SUVs fast enough. Remember the Ford Excursion? Launched in 1999 it was the ultimate expression of excess and the low gasoline prices America had ever seen. Say what? Yep, adjusted for inflation, 1998/1999 was significantly lower than the nostalgic pricing of the 1950s and that drove the sales of ever bigger vehicles with big engines.

Simultaneous to the rise in “big SUV” was the realization that problems were brewing. George W Bush had strong ties to the domestic oil industry, as did his VP and his father. At the start of his first term in 2001 he and a task force he appointed decided that America was too dependant on foreign energy supplies. Although he was opposed to the Kyoto protocol, Bush had a kind of carbon emissions concept of his own: energy independence.

By 2006 the United States was gripped by high gasoline prices yet again and by 2008 adjusted for inflation, gasoline prices were the highest since 1918. Because oil is a global commodity, “drill. baby drill” will only get you so far. You see for every gallon of extra oil America extracts, OPEC nations could simply reduce production to keep prices high. So in addition to lifting a ban on offshore drilling, GWB also pushed for higher fuel economy targets. In 2008 Bush made a speech in which he said “in the long run, the solution is to reduce demand for oil by promoting alternative energy technologies. My administration has worked with Congress to invest in gas-saving technologies like advanced batteries and hydrogen fuel cells.”

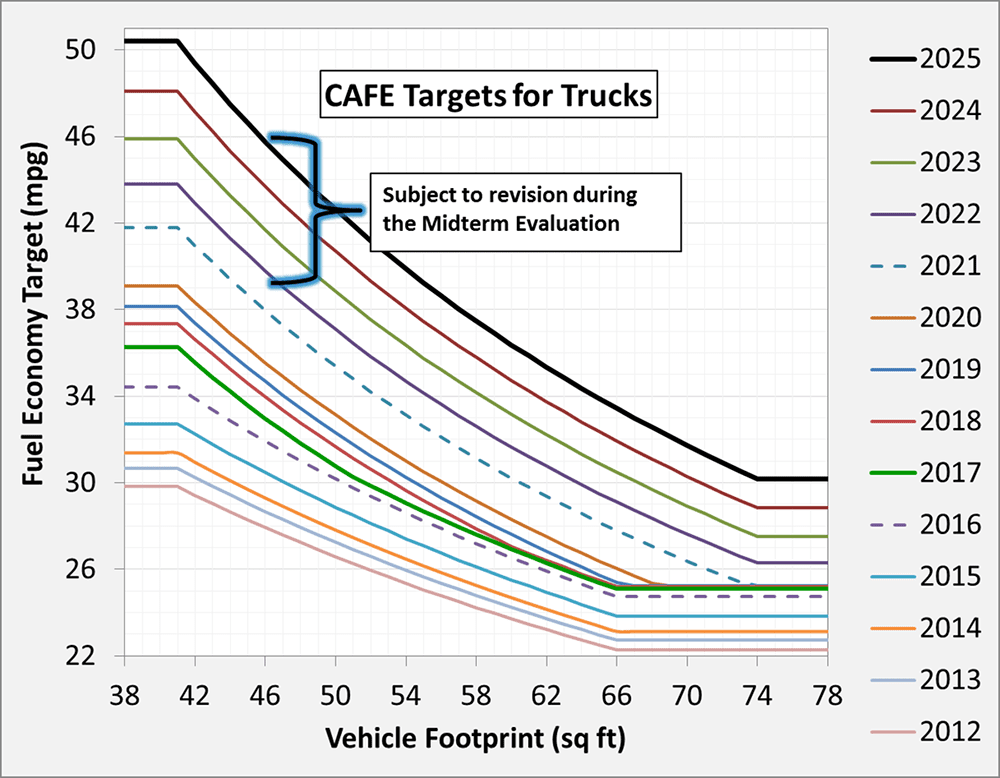

The solution was a revision to CAFE signed into law by GWB that went into effect with the 2011 model year. Not only did fuel economy targets rise, it introduced a new “sliding scale” for fuel economy as a result of pressure from auto makers and the public that wanted their big SUV cravings to be satisfied. The new “footprint model” operated this way: the smaller the footprint, the higher the MPG targets, the larger the footprint the lower the MPG targets. There were maximums and minimums of course, you couldn’t simply build a Simpsons “Canyonero” and get 1 MPG because every category had a “floor” if you will.

Trouble is: unintended consequences. You don’t have to be as efficient if you just make the truck bigger, but also if you make the truck too small like the Montana, the fuel economy target is unachievable.

One important thing to keep in mind when we talk MPG requirements is the calculation method. When CAFE was most recently updated (2007) the USA was still using a decades old MPG testing standard. This was updated in 2008 in order to make window sticker fuel economy more realistic. For whatever reason, CAFE’s rules were never re-written and the CAFE economy targets are still based on the old method of calculation. The older standards heavily benefit diesels, mild hybrids and full hybrids. So when for CAFE purposes a vehicle needs to get 50 MPG to comply, in reality a “40 MPG window sticker” vehicle like the Maverick is likely fine.

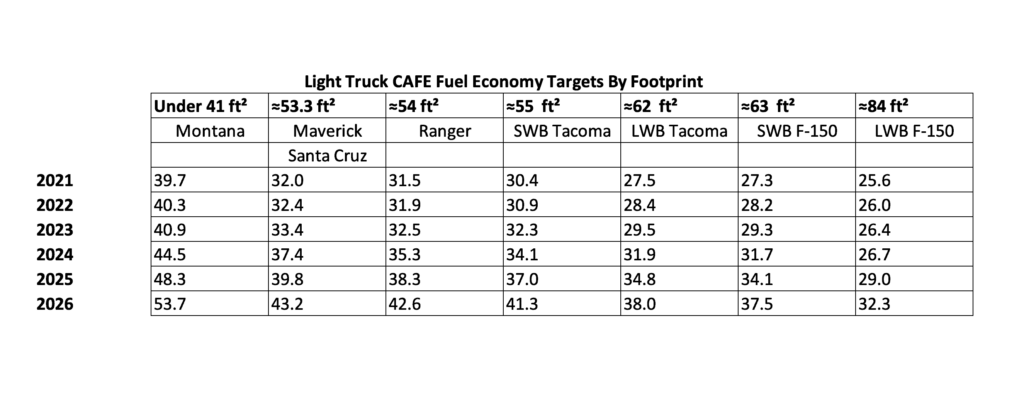

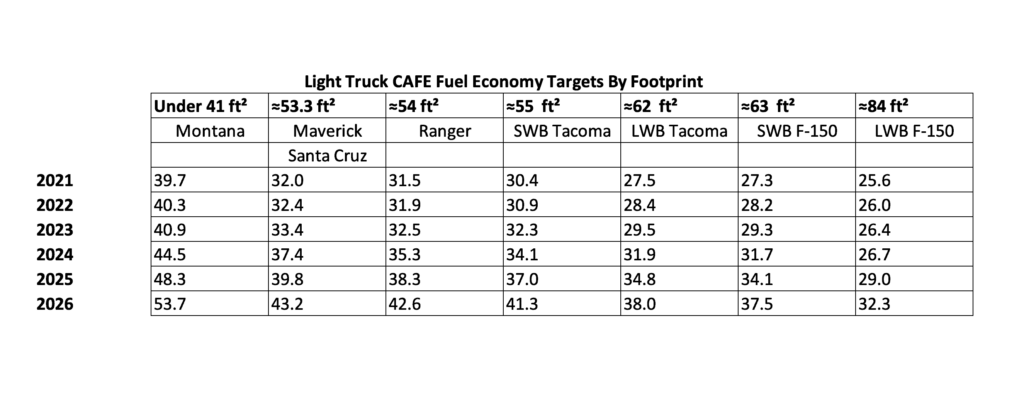

Check out the chart below for how the footprint impacts MPG requirements. For 2021 basically all ½ ton trucks must meet 25.6 MPG as calculated by the old MPG standard. Yes a short wheelbase F-150 would be up at 27.3, but that’s likely part of the reason it’s so hard to find a single-cab 1/2 ton truck these days. Customers don’t buy them and they screw up a company’s CAFE compliance.

A Ford Ranger, Tacoma, Colorado? 27.3-31.5 depending on the footprint. This is trickier, but it explains why some companies just pay the fines, and why mid-size trucks are more expensive (the cost of compliance is likely passed along). The Maverick? It’s only a hair smaller in “footprint” to the Ranger, so it needs to hit 32 MPG. This is how the Santa Cruz manages to comply without the hybrid that Ford puts in the Maverick.

Why did Ford bother with the Maverick Hybrid then? Because in 2026 it’ll need to be hitting 43.2 MPG. But more importantly, if the Maverick beats the CAFE requirement, Ford can use those “MPG credits as I call them to counterbalance F-150s that might not be in compliance. F-150 Lightnings also help the blend.

If GM were to bring something as small as a Montana (or a truly small truck) to the US, they would need to either make it a PHEV, a full EV, or be prepared to pay the fines, because rationally it’s unlikely to meet the 48+ MPG requirement for that “footprint” in 2025 without going in those directions let alone a 53 MPG requirement in 2026. Yes, GM could add a hybrid or just pay the fines, but if “small means cheap” then a small pickup that’s the price of an F-150 would be a different kind of market fail.